Texas Flood: How to Bust a Drought

I used a fancy machine-learning model called a random forest to predict the lake's elevation from my training data and was able to do a decent job predicting past lake levels from historical data. Since Lake Travis is currently over 53 feet below its normal elevation, I wanted to use my model to predict how much rain we'd need to fill the lake back up and end this drought.

I thought this was going to be a relatively easy task, after all I had already done the hard part of finding the data and building the fancy model. My plan was to dump a bunch of rain in the area, then see how my model reacted and write it up. I thought this couldn't take more than a week. Instead, what I got was a valuable lesson in machine learning model design--complicated is not always better.

Anyway, I'm getting ahead of myself. I first had to find a test data set to represent a period of heavy rainfall over Central Texas. I tried looking for data from a real tropical storm, but couldn't find anything useful. No one released data in the form I needed (basically a table with x and y coordinates and a value to indicate how much rain fell). So I gave up looking for tropical data and tried something else. I had heard about the so-called "Christmas storm" in 1991, where the lake rose 35 feet in a period of a few days in late December in response to heavy rains. I found data from NOAA about the rainfall rates in various places and tried plugging that into my model. As you can probably guess, a lot of things changed in the way NOAA reported measured rainfall in the time between 1991 and 2011-2012 (the timeframe on which I had trained my model). Very few of the stations present in the training data from 2011-2012 were also in the 1991 data. So I tried interpolating between them, but there were ultimately too few data points in common to make this a viable option.

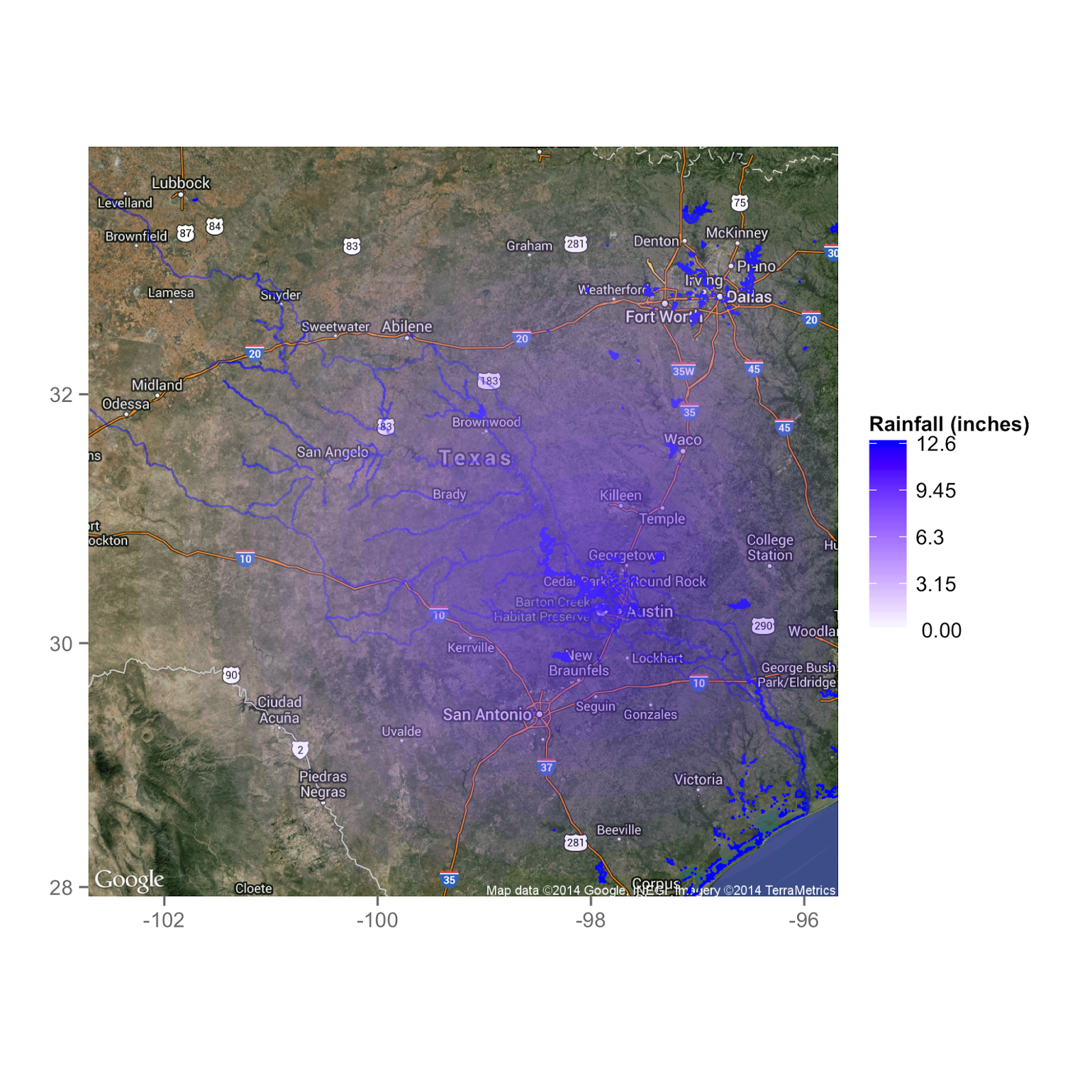

Then I realized that I could simulate a heavy rainfall pretty easily myself. All I needed to do was pick a function that has a maximum at its center, and declines smoothly so that there's less rain the farther you are from its center. So I picked the function every astronomer uses when they want to parameterize something they know very little about, the Gaussian. I set my Gaussian to have a peak rainfall of 12 inches and a dispersion of 100 miles. That means that at about 118 miles away from its center, (which I set to Lake Travis) the rainfall would drop to half its maximum value, or 6 inches. It would then decrease to (practically) zero for distances much greater than 118 miles.

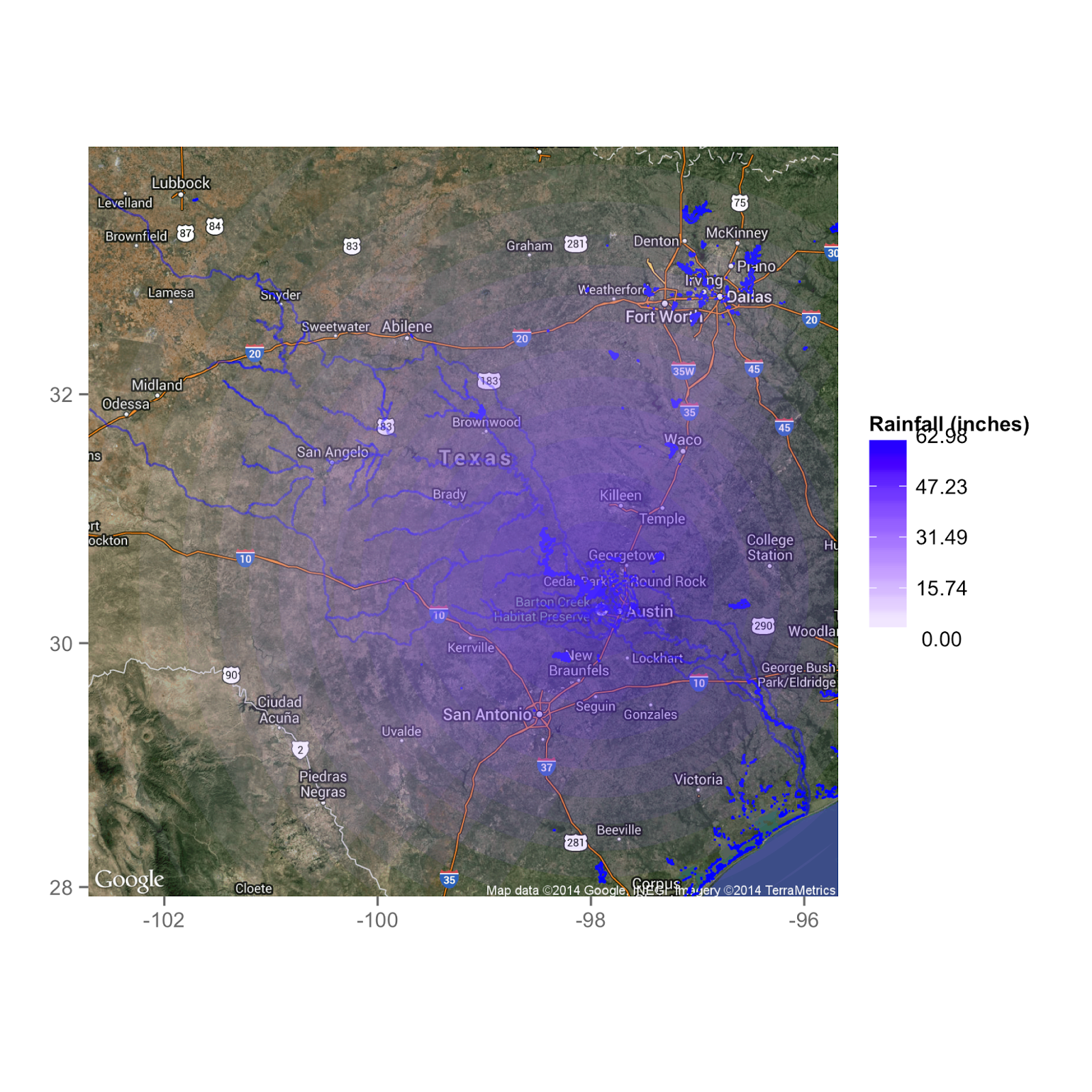

Here's what my simulated flood looked like:

|

| Map showing the distribution of rain during my simulated flood. I assumed that all of this rain was dropped in a 24 hour period. Source Code |

I tried reformulating the problem to predict changes in the lake's elevation (I probably should have been doing this all along), but no luck. I also implemented feature scaling--the process of scaling every one of your dependent variables to have zero mean and unit variance. None of these had any effect on my model's predictions, although they were all good improvements to the model's design.

I was now fairly sure I was guilty of the mortal sin of overfitting. This is what happens when your model is overly complicated for the task at hand and you experience high variance. A good example of this would be instead of fitting a straight line to data, you fit a 34th order polynomial that passes through every data point. This is technically a "good fit" to the training data, however if you want to use this model to predict what will happen when a new unseen data point is included, it will likely wind up giving a nonsense result.

Although overfitting is nasty little devil, there are standard practices, which I thought I was following, that are designed to combat it. For instance, one can "hold out" a portion of the training data, say 10%. Then you can train your model on the remaining 90% and use the left out portion as a check to see how good a job your model does at predicting the result of data points it hasn't yet seen. This process is known as cross-validation and is a standard tool in any modeler's toolkit. I thought the bootstrapping in my random forests would take care of this, but apparently it wasn't enough.

When your model is not producing a good fit, it's tempting to keep trying more complicated models until things improve. However, we need to discriminate between the problem of high bias (a crappy fit to your training data) and the problem of high variance (predictions of new test data not making sense). A more complicated model will almost always reduce bias, but sometimes it also increases variance. So I tried the opposite approach and used a less complicated model. I reasoned that if I could keep the bias in check, I'd probably bring down the variance and get some predictions that made more sense.

I decided to use a technique known as Ridge Regression. Ridge is a form of linear regression (think least squares), but with a penalty placed on the regression coefficients so they don't get too large and allow overfitting. This process is known as regularization and is set by the regularization parameter. For small values of this parameter, the model cares more about fitting to the data than minimizing the regression coefficients (bias is low, but variance is high). As this parameter is increased, it causes the model to focus more on minimizing the regression coefficients (driving variance down, but with an accompanying increase in bias). Somewhere in there is a Goldilocks value for the regularization parameter, and this is found by running many models varying its value. Cross-validation is then used to determine which model did the best on the held-out data, and that model's parameter's value is used. The sklearn package in Python has a method called RidgeCV that takes care of this for you.

To combat the increase in bias I thought I would get from using a linear model, I went out and grabbed a lot more training data. Instead of using only data from 2011-2012 to train my model, I used data from 2007 all the way through 2012. I ran this through my code and got a much better result. First, a look at how well my model was able to fit the historical data (quantifying the level of bias).

|

| How well my model was able to fit the training data (compare to the Random Forest in my last post). Source Code |

|

| Courtesy of the LCRA's website |

For a similar rainfall event, they got a 35 foot increase! So one of two things are going on: either my model still isn't a great fit, or conditions in 1991 were different enough from those in my 2007-2012 training set such that 1 foot of rain doesn't translate into the same amount of water in streams and lakes. The latter seems possible if the ground saturation is significantly different from the dry conditions we've been experiencing during the 2007-2012 period. Of course, it's also probable my model still isn't that great of a fit.

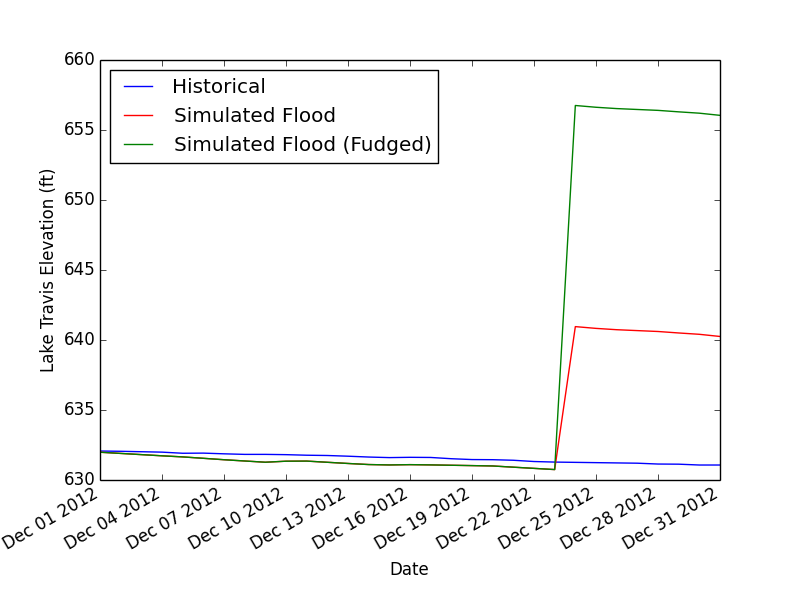

So I decided to fudge things a little and see what happened. That graphic above also lists peak stream flows for a few important streams that flow into Lake Travis. Rather than have my model try to predict these from the rainfall, I set them manually and re-ran things.

|

| What actually happened in 2012 (blue) versus what my model predicts would have happened with the flood shown in my first plot. Source Code |

This fudged model now predicts a 25 foot rise, closer to the 35 foot rise observed during the Christmas storm. I think that's pretty good, especially since there's no guarantee that the actual storm looked anything like my fake flood (despite the agreement of a few rainfall totals around Austin). It's also important to note that the 1991 flood caused the LCRA to take extraordinary actions in managing the flood (e.g. they let Lake Travis fill to the brim before releasing floodwaters downstream) and these are likely significantly different from the natural in/out flows encoded in the training data. In other words, my training data don't include the way human beings react to manage severe floods.

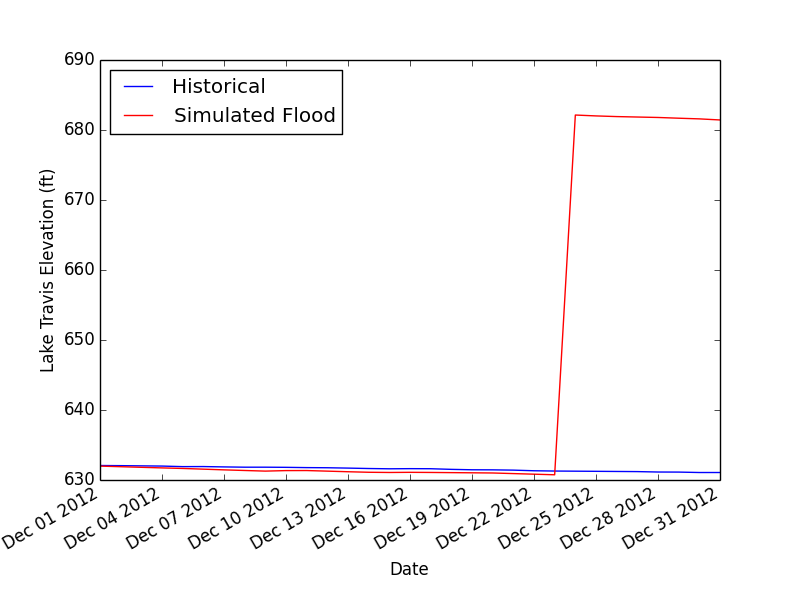

So, ignoring all these issues for a moment, let's just use my model to see what kind of a flood we'd need to fill up Lake Travis tomorrow.

|

| Dumping 5 feet of rain on Central Texas would fill it up in a day. |

It turns out we'd need 5 times as much rain as in my test scenario--5 feet over Lake Travis, and 2.5 feet at a location 118 miles away! So much for busting the drought with a tropical storm. Now, I should add that we've already seen that my model tends to under-predict lake level rises (at least compared to the Christmas storm). So maybe we don't need quite as much rain to get that 53 foot rise to fill the lake up. But I think it's a safe bet that one tropical event won't be enough.

|

| The rainfall even my model predicts we'd need to fill up Lake Travis from its current elevation of 53 feet below normal. |

Leave a Comment